If you were paying attention in history class, you’ll recall the Underground Railroad wasn’t a railroad at all. Rather, it was a fluid network of locations where freedom seekers sought refuge from slave catchers on their way to a life out of bondage.

“What came to be called the Underground Railroad were the networks of assistance that emerged in response to the reality that freedom seekers were showing up,” said Illinois historian Larry McClellan. “Those reacting to the movement of freedom seekers picked up on the most compelling new language of the day: the new technologies and terms associated with the coming of the railroads across America.”

There are many Underground Railroad sites in Illinois that were used in the 19th century, before and during the Civil War. There’s even a memorial in a Maywood McDonald’s restaurant parking lot that honors journeys through the Underground Railroad.

Following is a look at some of the sites and what to expect if you decide to visit.

One caveat: Information about the Underground Railroad is hard to lock down with total accuracy. Details are often found in extremes — there’s either comprehensive minutiae on a specific freedom seeker’s journey, or a story steeped in generalities. Because the workings of the Underground Railroad were very secretive, accurate records are, in many instances, rare or nonexistent.

Here, we did our best to cross-reference Illinois locations with numerous sources, including the National Park Service: Network to Freedom list of sites. The Tribune visited as many sites on the Network to Freedom list as we could, given time constraints, distance or ongoing site construction.

Chicagoland (organized by county)

Cook County

African American Heritage Water Trail

This stretch of the Little Calumet River, beginning at the Cook County Forest Preserves’ Beaubien Woods and ending in south suburban Robbins, brims with the history of freedom seekers who followed its course in their escape and free Black Americans who settled along its banks.

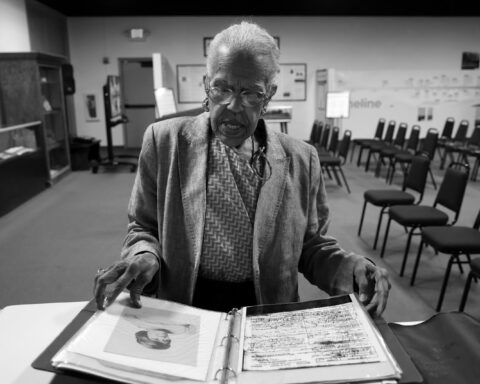

Historian Larry McClellan gives tours at certain times of the year, telling stories about some of the thousands of freedom seekers who traversed the area in search of safety and community. The Ton Farm (described below) is along the route, as is the Dolton Ferry and Bridge that provided a crossing for escapees on their way to Canada via Chicago or Detroit. The African American Heritage Water Trail is part of the Calumet Heritage Area.

Address: Beaubien Woods Boat Launch, East 132nd Street, east of South Greenwood Avenue, Chicago

Hours: Open year-round from sunrise to sunset.

What to know: The 7-mile trail requires those taking to the water to be experienced paddlers or traveling with an experienced guide. Several boat ramps along the trail allow visitors to paddle smaller portions of the waterway.

Amenities: Beaubien Woods has parking, accessible portable bathrooms from May through October, and an accessible picnic grove during the same season.

More info: 312-863-6250, openlands.org/paddle-illinois/african-american-heritage-water-trail

Graceland Cemetery

Chicago’s location along Lake Michigan and the large number of free Black activists helped it become a major destination for freedom seekers. Graceland Cemetery, established in 1860, became the final resting place of many Underground Railroad conductors, freedom seekers and abolitionists.

Among the cemetery’s sculptural tombstones and winding paths, their number includes John and Mary Jones; Emma Jane Gordon Atkinson, believed to be one of the “Big Four,” the four Black women who led the Quinn Chapel AME’s work with the Underground Railroad; Chicago’s first pharmacist, Philo Carpenter, and his wife, Ann Thompson Carpenter, who sheltered an estimated 200 freedom seekers; and L.C. Paine Freer, who would chase slave catchers on horseback.

Address: 4264 N. Clark St., Chicago (Greenwood Gate open during main entrance renovation)

Hours: 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. weekdays; 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekends. Open until 4 p.m. fall and winter weekdays.

What to know: The cemetery’s place in Chicago’s history and its architecturally impressive landscape have helped it become an attractive destination for Chicagoans and tourists. It remains a working cemetery across its 119 acres, and has burial search services for those interested in genealogy or the history of those buried at Graceland.

Amenities: During the cemetery’s renovation of its main entrance, the visitor center, parking lots and office are closed to the public. Restrooms available outside the chapel. Self-guided audio tours available online.

More info: 773-525-1105, gracelandcemetery.org

Jan and Aagje Ton Farm

In 2019, the Jan and Aagje Ton Farm became part of the National Park Service Network to Freedom program, which promotes the history of resistance to enslavement in the United States. Formerly known as the Ton Farm, the site is also home to Chicago’s Finest Marina. The Tons were one of several Dutch families that settled in the area between 1849 and 1853. From the 1830s until the Civil War, many people escaping enslavement fled to the Calumet region. Freedom seekers used what was known as the “Riverdale Crossing,” now the Indiana Avenue Bridge just west of the marina, and then sought refuge with Dutch settlers before they continued north.

Address: 557 E. 134th Place, Chicago

Hours: Call ahead to book a tour.

What to know: Along with plenty of available parking, the site is located in a residential area, with a Divvy bike station nearby, at the Altgeld Gardens Library branch.

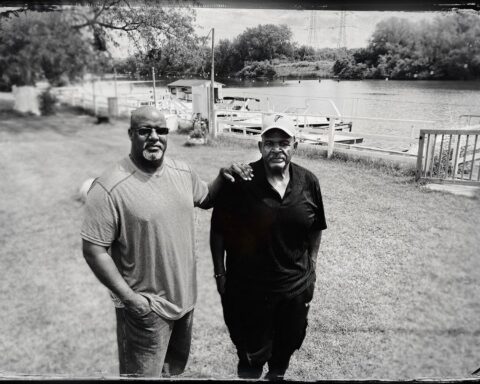

Amenities: The Black-owned marina sits next to the Little Calumet River. During warmer months, kayakers and boaters can be seen floating by. The marina is one of the stops on the African American Heritage Water Trail, which honors the Black history of those who settled along the river, from freedom seekers to those in the Civil Rights and environmental justice movements. Owner Ronald Gaines Sr. is hoping to expand the marina to host reunions and weddings.

More info: 312-402-5557, facebook.com

Little Calumet River

This river was a vital guide for freedom seekers crossing into Chicago’s south suburbs and neighborhoods — an estimated 3,600 to 4,500 formerly enslaved people did so. It crosses through parts of what are now the Cook County Forest Preserves, and also hosts the African American Heritage Water Trail, which begins at Beaubien Woods.

Address: 1562 Water St., Blue Island

Hours: The site is open year-round, sunrise to sunset.

What to know: Paddling through portions of the river requires experienced paddlers or traveling with an experienced guide. Several boat ramps along the trail allow visitors to paddle smaller portions of the waterway.

More info: 312-863-6250, openlands.org/projects/little-calumet-river

Quinn Chapel AME Church (Chicago)

What began as a seven-member prayer band formed into an official congregation of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1847. The name was chosen in honor of Bishop William Paul Quinn, an AME missionary who organized many churches in Indiana, Illinois and Missouri. The current building has stood since 1891, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. As the oldest Black church in Chicago, Quinn Chapel was a station for the Underground Railroad. After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the church congregation created a Vigilance Committee to watch for bounty hunters trying to drag Black Chicagoans into slavery.

Address: 2401 S. Wabash Ave., Chicago

Hours: Worship service is at 10 a.m. Sundays. Call ahead for individual tours.

What to know: The original site of Chicago’s Quinn Chapel sat on the southwest corner of Jackson and Dearborn at Federal Plaza in the Loop, only to be burned down in the Great Chicago Fire. One of the current church’s pews sits in the Smithsonian Museum. Notable Black icons have spoken in its pulpit, including George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, Paul Lawrence Dunbar and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Renovations are underway on the second floor and the lower level to make an on-site Underground Railroad museum, according to senior pastor Troy Venning.

Amenities: Restrooms, ADA compliant, parking lot and street parking available. It’s next door to the former home of the historical Chicago Defender newspaper.

More info: 312-791-1846, quinnchicago.org

Ten Mile Freedom House Marker

A McDonald’s might seem like an unlikely location for an Underground Railroad site, but in Maywood, one is home to a humble monument marking the former Ten Mile Freedom House. Once a resting place for rural farmers en route to Chicago, the house became a refuge for freedom seekers, but was torn down in 1927.

In its place, a set of railroad tracks leads to a marker with broken shackles and a plaque honoring the Underground Railroad and its most well-known conductor, Harriet Tubman.

Address: 11 N. First Ave., Maywood

Hours: Accessible year-round in parking lot

Underground Railroad Memorial Garden

This garden pays tribute to Jan and Aagje Ton, Dutch immigrants whose farm along the Little Calumet River became a safe haven for freedom seekers. It also honors all who took a stand against slavery, and was created by a local Boy Scouts troop in 2011.

Address: 15924 S. Park Ave., South Holland

Hours: Call for visiting information.

What to know: The garden is located on the grounds of the First Reformed Church of South Holland. The church has service at 9:30 a.m. Sundays, and its building is otherwise open from 9 a.m. to noon on weekdays.

More info: 708-333-0622, frcsh.org

DuPage County

1846 Israel Blodgett House

One of the oldest homes in Downers Grove and now known as the Downers Grove Museum Pioneer home, the house was built by Israel Blodgett and his wife, Avis. The Blodgetts were abolitionists and supposedly hid freedom seekers in the upstairs quarters. The home was moved to 812 Randall St. in the late 1800s, but eventually returned to its original location — now part of the museum campus and the surrounding Wandschneider Park — and restored in 2008. While rehabbing the structure, workers found abolitionist newspapers stuffed into the walls, offering some proof the Blodgetts assisted freedom seekers.

More than 40 years later, the Blodgetts’ son Charles built a Queen Anne-style home on the land, which is now the museum’s main building and office. Israel and Avis’s son Henry W. Blodgett was an abolitionist and a judge who, as Kate Masur writes in “Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction,” called on the Illinois legislature to repeal all existing anti-Black laws, rather than pass another proposal to criminalize the act of bringing free or enslaved African Americans into the state.

Address: 831 Maple Ave., Downers Grove

Hours: Noon to 4 p.m., Tuesdays-Thursdays; 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., second and fourth Saturdays of the month

What to know: The entrance is off Maple Avenue on Belden Avenue; drive straight back to find parking near the Montrew Dunham History Center. Self-guided tours of the 1892 Charles Blodgett House can take place any time during the museum’s hours, but only guided tours by appointment are allowed for the 1846 Blodgett House. The site is a 15-minute walk from the Fairview Avenue Metra station.

Amenities: Restrooms, walking path, picnic tables, park benches, ADA compliant

More info: 630-963-1309, dgparks.org/downers-grove-museum-exhibits

Blanchard Hall at Wheaton College

Wheaton College, founded in 1860, was surrounded by an abolitionist community, and Blanchard Hall was a station on the Underground Railroad. The college’s first president, Jonathan Blanchard, and his wife, Mary, were abolitionists who helped freedom seekers on their way to Chicago and onward to Canada by harboring them in their home. Students would later write accounts of how formerly enslaved people found a safe harbor in the college building on their way to freedom. Blanchard Hall, known as Old Main on campus, was built in various sections beginning in 1853 and completed in 1927. The limestone building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Address: 501 College Ave., Wheaton

Hours: Open during campus business hours

What to know: Located in the center of the Wheaton College campus just north of the Billy Graham Center, Blanchard Hall features exhibits in its lobby about freedom seekers and African American history.

Amenities: Restrooms, visitor parking, ADA accessible, exhibits in the lobby, water fountains

More info: 630-752-5000, wheaton.edu

Graue Mill and Museum

While this 170-year-old flour-producing mill remains one of the few of its kind still in operation, its history as a “station” on the Underground Railroad also left a mark, according to longtime Underground Railroad researcher and historian Glennette Tilley Turner. During tours of the Oak Brook mill, staff members recount how anti-slavery German immigrant Frederick Graue would hide freedom seekers in the mill’s basement.

Address: 3800 York Road, Oak Brook

Hours: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Thursdays and Fridays; noon to 4 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays.

What to know: Tours and programs showcase life in the 1850s and ’60s, and weekend demonstrations offer examples of milling, spinning and weaving. Admission is free. Parking is on the west side of Spring Road, one block west of York Road.

More info: 630-850-8112, grauemill.org

Sheldon Peck Homestead

Abolitionists Sheldon and Harriet Peck built their home in 1839, making it the oldest existing home in Lombard. As a folk artist, Sheldon Peck would travel to Alton, Illinois, for work, providing a key opportunity to help freedom seekers reach northern Illinois. Peck was considered radical because he believed in the immediate end to slavery and equal rights, and the couple could have had as many as seven freedom seekers staying in their home at a time.

The last Peck descendant to live in the home was Alyce Mertz, who lived there until her death in 1991. Her son, Allen Mertz, inherited the home after Alyce’s death and donated it to the Lombard Historical Society. The homestead is a verified Underground Railroad site and, in 2011, was inducted into the Network to Freedom.

Address: 355 E. Parkside Ave., Lombard

Hours: Noon to 4 p.m., Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, February-November

What to know: There are only four parking spots. Visitors are encouraged to park at the Lombard Common/Paradise Bay Water Park lot across the street on St. Charles Avenue. The homestead is also a 12-minute walk from the Lombard Metra station near Main Street.

Amenities: Restrooms, ADA compliant, limited parking

More info: 630-629-1885, lombardhistory.org/peckhomestead

Lake County

Mother Rudd Home Museum

The oldest building in Warren Township and one of the oldest in Lake County, the home dates to the 1840s and is named for Mother Rudd, aka Wealthy Buell Harvey Rudd.

Over the years, the house has functioned as a post office, inn, stagecoach stop and town hall. Documentation of the site as a stop on the Underground Railroad does not exist; however, Joe Lodesky of the Warren Township Historical Society said the home is considered an Underground Railroad site through local lore, given the county was heavily Republican at the time and the Des Plaines River runs next to it. A barn on the property, now only partially standing, was believed to house freedom seekers.

Amos Bennett, the first African American settler in Lake County and a child of freedom seekers, settled in the area in 1834, according to a 1993 Chicago Tribune story. A plaque to honor Bennett’s contribution to the area was placed near the remnants of the Rudd barn this year.

Address: 4690 Old Grand Ave., Gurnee; turn onto Kilbourn Road from Grand Avenue (Illinois Route 132)

Hours: 9:30-11 a.m. Tuesdays. Call ahead to schedule group tours and get open house information.

What to know: Traffic can be heavy during the summer, especially on weekends, because the house is located east of Six Flags Great America and the Gurnee Mills shopping mall on Grand Avenue. The second floor of the home also houses the Warren Township Historical Society, which is open to the public.

If you have time, drive 11 minutes to Waukegan to visit the African American Museum at the England Manor, 503 N. Genesee St. The owner of the museum is Sylvia England and a tour of her home takes you through her ancestors’ story from their time in Africa to present day, including the Underground Railroad. The museum encourages visitors to share their own stories of culture and family.

Amenities: Parking, ADA accessible, restroom, park area, adjacent to Des Plaines River bike trail

More info: 847-263-9540, motherrudd.org

Will County

Crete Congregational Church and Cemetery

The National Park Service added this church property and cemetery to its Network to Freedom listings in 2018. The church is the sole existing south suburban building associated with the Underground Railroad.

Church members aided freedom seekers traveling through Illinois, and the area is known for having passed one of the earliest anti-slavery resolutions in the state. Freedom seekers like Caroline Quarlls, who fled from St. Louis in 1843, utilized the Underground Railroad network in the area to make their way to Canada, traveling through Indiana and Detroit on the way.

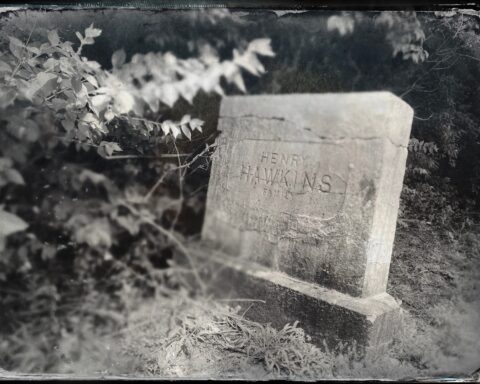

The cemetery is also part of the Network to Freedom, as key players in the abolition movement are buried in the cemetery, including Samuel Cushing.

Address: 550-570 W. Exchange St., Crete

Hours: Call ahead for an appointment.

What to know: Since early 2022, efforts have been underway to turn the church into the Crete Historical Museum, thanks to efforts by the Crete Area Historical Society. A golf and dinner fundraiser set for Sept. 24 will raise money for the building’s restoration. While the cemetery is open to the public year-round, appointments are required to visit the church.

More information: 708-414-0002, cretehistorical.com

I&M Canal Headquarters

The Illinois and Michigan Canal was instrumental not only in boosting national trade and developing Chicago as a major U.S. city, but also in the admittance of Illinois as a free state. The canal stretched from Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood to LaSalle in Will County, connecting a water route that could transport goods and people as far south as St. Louis and New Orleans, and east to Buffalo, New York.

Even before the I&M Canal was completed in 1848, freedom seekers would follow its path as they headed for Chicago, aided by abolitionists along the route. Canal officials such as its first superintendent, Peter Stewart, and nearby residents faced criminal charges and retaliation for helping freedom seekers.

The Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Area, made up of 60 cities and towns, was designated in 1984 as the first of its kind. The canal headquarters was built around 1836, just as work on the canal began. It was the first building in Lockport, and the National Park Service deemed it northern Illinois’ most significant pre-Civil War public building still in existence. It is now the home of the Will County Historical Museum, containing land deeds signed by former presidents, Abraham Lincoln’s visiting card, and the last surviving rosebud from his funeral.

Address: 803 S. State St., Lockport

Hours: Open noon to 4 p.m., Wednesday-Sunday

What to know: For those interested in genealogical research, you’ll find 90,000 Will County obituaries, as well as death certificates of African Americans in Will County from as far back as 1878. Admission is free, but donations are welcome. Those who want to explore more I&M sites can also check out the last existing I&M Canal Toll House in Ottawa, approximately one hour west of Lockport.

Amenities: Restrooms, plenty of street parking, ADA accessible, and restaurants nearby

More info: 815-838-5080, willhistory.org

—

Additional Chicagoland sites with no existing physical structure: Batchelder Home, Samuel and Elizabeth Cushing Farm, John and Mary Jones House, McCoy Homestead

Northern Illinois

Charles Hibbard House

This McHenry County home is also known as the Cupola House for its octagonal cupola on the roof. The home had a secret underground room with a hidden entrance, and when it was safe for freedom seekers to stop there, the Hibbards would hang a light in the cupola as a signal.

Address: 413 W. Grant Highway, Marengo

What to know: Private residence not open to public

More info: wonderlakelive.com/national-register-landmarks-mchenry-county

I&M Canal Toll House

Initially one of four stops to pay tolls along the I&M Canal, the Ottawa toll house is the last still in existence. Built in 1849, it is now a museum with artifacts from the lives of toll collectors, who slept and worked in the 16-by-24-foot building.

Even before the I&M Canal was completed in 1848, freedom seekers would follow its path as they headed for Chicago, aided by abolitionists along the route. Canal officials such as its first superintendent, Peter Stewart, and nearby residents faced criminal charges and retaliation for helping freedom seekers.

Address: 1221 Columbus St., Ottawa

Hours: Call for an appointment.

What to know: Donations are encouraged for tours

More info: 815-434-2737, pickusottawail.com/attractions/im-canal-toll-house

John Hossack House

John Hossack made history for aiding freedom seeker Jim Gray, who was being remanded under the Fugitive Slave Act in 1859. Before he was taken in custody, Hossack and other abolitionists in the courtroom assisted Gray to escape from the court in a carriage.

Address: 210 W. Prospect St., Ottawa

Hours: Private residence, not open to the public. Awesome Ottawa tours sometimes drive past the home.

More info: 309-678-7716

Lucius Read House

The Read House, constructed in the early 1840s, was one of three Underground Railroad stops in Byron. Other families in Byron would offer their barns as places for freedom seekers to hide. The current Read House showcases Lucius Read’s headstone, a letter he wrote to his stepson, and a wooden box similar to one that Henry Brown used to mail himself from Virginia, a slave state, to the free state of Pennsylvania. Folks can step in and try it out. There’s also information about modern-day slavery, from sex trafficking to forced marriage and forced child labor.

Address: Byron Museum, 110 N. Union St., Byron

Hours: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., Wednesday-Saturday. Open February through December; January by appointment. Free admission.

What to know: The museum’s collection will soon grow to include an authentic manilla, a metal bracelet used as a form of currency in slave trading, said Marian Michaelis, the museum’s executive director. An auctioneer struck up a conversation with Michaelis while visiting the museum, only to ultimately offer the artifact for display.

Amenities: Restrooms, free street parking, ADA accessible

Phone: 815-234-5031, byronmuseum.org

Newsome Park

A boxcar arrived in Elgin carrying more than 100 freedom seekers in 1862. The formerly enslaved people found homes and jobs, and quickly founded the Second Baptist Church. The church existed for nearly a century on the site of what is now Newsome Park, named for two unrelated freedom seekers, Arthur Newsome and Peter Newsome, who took that boxcar to freedom.

Address: 280 Kimball St., Elgin

Hours: Sunrise to sunset, year-round

More info: elginhistory.org/newsome-park

Ottawa

Ottawa was an Underground Railroad stop that potentially helped thousands of freedom seekers on their journeys. For those looking to see the safe houses and sights essential to those escapes, two-hour walking and driving tours delve into the town’s history.

The tour includes details on the Illinois and Michigan Canal’s use for transporting freedom seekers; Gabriel Geiger, a Black man who was recorded as the first to vote in Ottawa; and the area where abolitionist John Hossack and others aided Jim Gray to freedom. Gray was one of three enslaved people who escaped in 1859 from owner Richard Phillips near New Madrid, Missouri. Hossack and others were tried in Chicago. Ottawa was also the location for the first Lincoln-Douglas debates.

Address: Tours start at the tour office at 624 Court St., Ottawa

Hours: Tours run every day from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

What to know: The tours costs $35 and have a maximum capacity of 14 people. Individual tours are also available in an SUV. Although the vehicles don’t have wheelchair lifts, most tours can be given from vehicles without having to get out of them.

Amenities: Restrooms available in tour office. Free parking in the historic business area.

More info: 815-343-4940, awesomeottawatours.com

Owen Lovejoy Homestead

The homestead belonged to Owen Lovejoy, an abolitionist minister and congressman, and brother of murdered abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy. In May 1843, Lovejoy was indicted on a charge of harboring two freedom seekers, but was acquitted.

It is said that Frederick Douglass stayed here, a half-mile from downtown Princeton, and docents can point out a hidden area above the stairs where freedom seekers hid. Lovejoy occupied the house from 1838 until his death in 1864. Lovejoy, a friend to Abraham Lincoln, was prominent in the abolition movement and a founder of the Illinois and national Republican parties. In the rear of the homestead sits The Colton School, also known as The Red Brick School, a one-room school moved from a farm nearby to its present location.

Address: 905 E. Peru St., Princeton

Hours: Tours take place 1-4 p.m. Fridays through Sundays from May through September. An annual homestead festival takes place the second weekend in September.

What to know: Suggested donations are $3 for adults. It’s about a two-hour drive from Chicago. A tour of the homestead also includes one of the school.

Amenities: Free parking available in the residential and business area.

More info: 815-879-9151, owenlovejoyhomestead.com

Central Illinois

Asa Talcott House

Asa and Maria Talcott were founding members of Jacksonville Congregational Church. Many Underground Railroad conductors went to the abolitionist Talcotts for supplies, and the barn behind their home was a place for freedom seekers to hide. Underground Railroad historian and researcher Glenette Tilley Turner writes of Talcott’s work with Black Underground Railroad conductor Benjamin Henderson in her 2001 book, “The Underground Railroad in Illinois.”

Address: 859 Grove St., Jacksonville

Hours: 1-4 p.m., Wednesdays, Saturday and Sunday, or schedule an appointment.

What to know: The Talcott House became home to the Jacksonville African American History Museum in June 2022. Visitors follow a historical timeline through the lens of Black Americans in the post-Civil War era, into the Civil Rights movement and the present-day work of Black Lives Matter. There is a suggested donation of $5 for adults and $3 for students.

More information: 217-299-6017, facebook.com

Beecher Hall at Illinois College

Illinois College was said to be at the center of the abolitionist movement due to its location between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. Students, professors and trustees of the college were active with the Underground Railroad, helping freedom seekers on their escape, hiding them in campus buildings, and sometimes facing criminal charges and fines for their actions.

Edward Beecher, brother of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe, was the college’s first president and helped found the Illinois Antislavery Society in 1837. Beecher Hall is named for him.

Address: 1101 W. College Ave., Jacksonville

Hours: Open during college operating hours.

What to know: The nearby Turner Junior High School offers guided tours of the historic areas of Jacksonville, including the campus. The Visitors’ Bureau of the Jacksonville Area Chamber of Commerce also has brochures with more information on the campus’ past as an Underground Railroad site.

More info: 309-678-7716, nps.gov/nr/travel/underground/Beecher_hall.html

Dr. Bezaleel Gillett House

After Dr. Bezaleel Gillett bought this 10-acre property in 1838, he hid freedom seekers in an abandoned cabin or shack on the land. The building may have had a trap door and a secret room to aid the formerly enslaved people as they traveled north.

Address: 1005 Grove St., Jacksonville

Hours: Call ahead for information on tours.

What to know: While the structure used to hide freedom seekers no longer exists, the Gillett House is now part of the Illinois College campus.

More info: 309-678-7716

Dr. Hiram Rutherford House

This Oakland, Illinois, residence was built in 1847, the same year its owner, abolitionist Dr. Hiram Rutherford, went up against Abraham Lincoln in a court case involving a family of freedom seekers in Illinois.

Kentucky enslaver Robert Matson would bring seasonal workers for his Illinois farm, then return south in the fall. Since Anthony Bryant, one of the enslaved men, stayed in the free state of Illinois year-round as an overseer, he gained his freedom. But when Bryant heard his wife and four children would be sold when they returned to Kentucky, the family fled, with Rutherford’s help.

Matson sued Rutherford and a second man for helping the Bryants and depriving him of his “property,” and Lincoln was his attorney. Despite Matson’s argument that the Bryants were Kentucky residents and therefore legally enslaved, the Bryants won and relocated to Africa.

Rutherford met his second wife, Harriet Hutcherson, at the trial, and the couple would have nine children and raise two Black children as well.

Address: 14 Pike St., Oakland

Hours: 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays from April through October. Call for appointment.

What to know: Parking is available on the street and nearby in the town square. The home is in a rural business area, about a two-hour drive from Springfield and down the way from Arcola, Illinois, where many Amish buggies occupy the street. Oakland is approximately a three-hour drive from Chicago. It’s not ADA accessible and has no air conditioning.

Amenities: Behind the Rutherford property sits a Mail Pouch Barn and the Museum of Agricultural History, where there is a piece of wood from the Lincoln-Douglas debate in Charleston, Illinois.

More info: 217-346-2154, nps.gov/nr/travel/underground/rutherford.html

Dr. Richard Eells House

In 1842, a freedom seeker from Monticello, Missouri, came to the house seeking aid on his way to Canada. Barryman Barnett, a free Black man, had spotted the freedom seeker, known to us only by his first name, Charley, swimming across the Mississippi and directed him to Eells’ house.

Eells attempted to hide Charley, but slave catchers were watching the Eells house. Charley was found along with his wet clothes inside the residence, indicating Eells’ assistance. Eells was arrested and charged with harboring and secreting a runaway enslaved person, a crime in Illinois at the time.

Today, the Friends of the Dr. Richard Eells House maintain the facility, which is Quincy’s oldest brick building. Built in 1835, it is furnished as it might have looked in its original state.

Address: 415 Jersey St., Quincy

Hours: Call ahead to schedule a tour.

What to know: It’s nearly a five-hour drive from Chicago. Eells House is down the street from the Quincy-Whig newspaper office. Inside, a newspaper article from the Quincy-Whig about Eells’ arrest can be seen. The house is open Saturdays from 1-4 p.m. from February through November, but tours must be scheduled in advance.

Amenities: Restroom, parking, not ADA accessible. The Quincy History Museum is nearby with a number of interesting artifacts from the town, including a copy of Barnett’s letter of emancipation, and a beautiful view of the town square.

More info: 217-223-1800, eellshousequincy.com

Galesburg Colony at Knox College

Galesburg and Knox College were founded in 1837 by anti-slavery advocates who came to Knox County from New York. Visitors can find information about Underground Railroad routes in western Illinois, a memorial for Freedom Seeker Susan Richardson, as well as exhibits on the Lincoln-Douglas debate.

Address: 52 W. South St., Galesburg (at Lincoln Studies Center, Third Floor, Alumni Hall)

Hours: 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. weekdays, September-May, closes at 4 p.m. June-August.

More info: 309-341-7757, knox.edu/about-knox/our-history/knox-and-galesburg-history/underground-railroad

General Benjamin Grierson Mansion

While his place in U.S. history is most notable for his eponymous Mississippi raid to cut Confederate supplies and free enslaved people (the John Wayne movie “The Horse Soldiers” portrays a fictional version of the raid), Jacksonville knew U.S. Union Gen. Benjamin Henry Grierson as a music teacher and father of seven.

Before he became a Union general, Grierson befriended Abraham Lincoln and wrote music for his first presidential campaign. The mansion he built on State Street incorporated a smaller brick home, and its previous owner, Garrison Berry, once provided shelter for Emily Logan. Logan had come from Kentucky with her enslaver, who had married Porter Clay of Jacksonville. When Logan realized she was living in a free state, she escaped and sought freedom, hiding in several Jacksonville sites of refuge before taking her case to the Supreme Court.

Address: 852 E. State St., Jacksonville

Hours: Tours are by appointment only.

More info: 309-678-7716, 217-243-5678; jacksonvilleil.org/business-directory/general-benjamin-grierson-mansion

Henry Irving House

Henry Irving aided freedom seekers in and around Jacksonville and nearby Farmingdale. As an active member of the Congregational Church, he was among the city’s active network of abolitionists. His obituary noted “his house was more than once a refuge to the freedom seekers.”

Address: 711 W. Beecher Ave., Jacksonville

Hours: Call for tour information.

More info: 309-678-7716

Jacksonville Congregational Church

Founded on anti-slavery beliefs and quickly nicknamed the Abolition Church, this congregation formed in 1833 with 32 members. Deacon Elihu Wolcott was known as the city’s chief conductor on the Underground Railroad, and parishioners readily provided shelter, clothing, food and transportation to freedom seekers.

Address: 520 W. College Ave., Jacksonville

Hours: Open 9 a.m. to noon Sunday-Friday; closed Saturday

What to know: The church remains an active place of Christian worship rooted in progressive ideals.

More info: 217-245-8213, facebook.com/jaxcucc

Jameson Jenkins Lot

While only this grass lot remains of the Jenkins family home, Jameson Jenkins’ role in the Underground Railroad left a lasting legacy. His work transporting goods provided excellent opportunity to assist freedom seekers, and Jenkins also drove Lincoln to the actual railroad station as he was heading to Washington, D.C., to take the oath of office as the nation’s new president.

Address: 516 S. Eighth St., Springfield

Hours: Open daily from 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m.

What to know: Along with being part of the Network to Freedom, the lot is located within the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield. The lot allows one to learn more through an app and QR code. Visitors can tour Lincoln’s home, take virtual tours around the park, and look into house exhibits and take in living history reenactments. Admission and tours are free, but reservations can fill up quickly. Parking fees are $2 per hour.

Amenities: The Lincoln Home National Historic Site has visitor and bus parking, accessible routes and accessibility maps, assisted listening devices, Braille tour booklets, wheelchair-accessible restrooms, and water fountains. Sign language interpreters available upon request with two-week advance notice.

More info: 217-492-4241, nps.gov/places/jameson-jenkins-lot.htm

Little Africa site

In the 1800s, most of Jacksonville’s Black population lived in an area of town known as “Little Africa,” bordered by West Beecher Avenue, South West Street, Anna Street and South Church Street. Of the more than 150 residents who lived there in 1860, many were formerly enslaved people who helped freedom seekers in their journey north. Notable residents included Underground Railroad conductor Ben Henderson and the Rev Andrew W. Jackson.

Address: 424 S. Church St., Jacksonville

Hours: Call ahead for tour information.

What to know: While not much trace of Little Africa exists in the present day, Jacksonville tours of Underground Railroad sites often include visits to the area where the neighborhood existed.

More info: 309-678-7716

New Philadelphia National Historic Site

After buying his freedom and his wife’s, “Free” Frank McWorter became the first Black person to found a United States town and establish a planned community in 1836. He named it New Philadelphia, and by mining for saltpeter in Kentucky, hiring himself out for work and selling lots in the town, he was able to raise money to buy the freedom of 15 more family members over the years.

McWorter attached huge importance to his freedom, as his great-great-granddaughter Juliet E.K. Walker wrote in “Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier.”

In the 1820 census, “the formerly enslaved Frank, rather than choosing a surname, had his name listed for the first time as Free Frank,” she wrote.

While New Philadelphia was dissolved in 1885 after McWorter’s death, archaeologists began excavating in 2003 in hopes of preserving the buried historical site. Work continues on a decade later; the New Philadelphia National Historic Site became a national park at the end of 2022.

Address: Broad Street at 2159E County Highway 2, Barry

Hours: Self-guided tours can be done any time. The site has an outdoor, covered kiosk with complimentary tours conducted by an augmented reality mobile app.

What to know: The nonprofit New Philadelphia Association manages the kiosk and virtual tour. The free app enables visitors to view 3D representations of buildings overlaid onto the existing landscape in their original locations.

Amenities: Free parking is available. It’s ADA accessible and outdoors on a grassy, cut path.

More info: 217-335-2716, newphiladelphiail.org

Old Knox County Courthouse

In 2021, this former courthouse was named a site on the Network for Freedom as testament to how polarized views on slavery were, even located far north of slave state borderlines. Susan Richardson escaped from her Illinois enslaver with her three children and came to Knox County. Over two years, her court case played out here, and while abolitionists hid Richardson in nearby Galesburg, her children were placed back with the enslaver. Richardson would risk recapture if she went to her children. She lived into her 90s.

Address: 33 N. Public Square, Knoxville

Hours: By appointment only. Sundays, 2-4 p.m., July-September.

What to know: The Knoxville Historical Society can arrange tours by appointment on Sundays in the summer.

More info: 309-289-2088, kchistoricalsites@outlook.com

Old State Capitol

During the Civil Rights movement, supporters built a re-creation of the Springfield Capitol building where Abraham Lincoln gave his “House Divided” speech, and where abolitionist figures such as John Jones and Frances Gage worked to strengthen the rights and freedoms of Black Americans. It was also the site of three important Illinois Supreme Court cases tied to the Underground Railroad involving Hempstead Thornton, Dr. Richard Eells and Illinois College student Samuel Willard.

Address: 1 Old State Capitol Plaza, Springfield

What to know: The building is not open to the public during restoration efforts, which began in January.

More info: 217-785-9363, dnrhistoric.illinois.gov/experience/sites/site.old-state-capitol.html

Pettengill-Morron House

Abolitionists Moses and Lucy Pettengill moved to Peoria in 1834 and started businesses and a church that promoted anti-slavery. Their original house used to sit where the Peoria Civic Center is now located.

The current site’s last resident, Jean Morron, donated the residence to the Peoria Historical Society along with historical artwork, furnishings and other items from both her family and the Pettengills. As a historical museum, the home also has a rotating schedule of temporary exhibits, and it is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Pettengills are buried in the nearby Springdale cemetery, and in 2021, the county added a marker designating them as conductors on the Underground Railroad.

Address: 1212 W. Moss Ave., Peoria

Hours: Every Thursday 10 a.m.-2 p.m. and by appointment

What to know: $10 tickets are available at 309tix.com

More info: 309-674-1921, peoriahistoricalsociety.com/houses

Porter Clay House

Elizabeth Hardin Clay moved to Jacksonville, Illinois, from Kentucky after marrying Porter Clay, and brought enslaved siblings Emily and Robert Logan with her.

When the Logans learned Illinois was a free state, they fled from the Clay home to avoid being sent back to Kentucky. They took refuge in Jacksonville’s Little Africa neighborhood, but Clay’s son-in-law captured Robert Logan, considered him enslaved, and took him to Kentucky, although a court ultimately ruled that Robert Logan was free. Members of the anti-slavery Congregational Church hid his sister, but the son-in-law tracked her down and captured her as well. But two years later, a jury ruled in her favor, and both Logans were granted their freedom.

Address: 1019 W. State St., Jacksonville

Hours: Call for information.

What to know: Woodlawn Farm’s Underground Railroad bus tours include visits to Jacksonville sites with ties to the Underground Railroad. The next four-hour tour is set for Oct. 15. Tickets are $20 for adults and $10 for children, and the deadline to register is Oct. 12. Call 217-479-4144 for more information.

More info: 309-678-7716

Woodlawn Farm

Michael Huffaker and his family helped freedom seekers on his farm, 5 miles east of Jacksonville. Huffaker built cabins on his property for free Black families, who then helped him raise cattle, horses and crops.

In 1840, Huffaker built the two-story brick home that still stands on the property. The Morgan County Illinois Historical Society bought the farm in 2003 to serve as a living history museum. Volunteers maintain the 10-acre property and host tours and events marking its place in Underground Railroad history.

Address: 1463 Geirke Lane, Jacksonville

Hours: The farmhouse is open to the public for tours May through September. Call 309-678-7716 to book a tour.

What to know: Parking is available on the farm. The home is in a rural area, about a four-hour drive from Chicago. One can visit numerous notable Underground Railroad sites in Jacksonville during the fall bus tour scheduled for 1-5 p.m. on Oct. 15. Tickets are $20, or $10 for children under 10. Reservation deadline is Oct. 12.

Amenities: Restroom available. The first floor is ADA accessible.

More info: Call 217-479-4144, woodlawnfarm.com, to book a spot on the biannual bus tour.

Southern Illinois

Alton

Alton is a southern Illinois river town that became a beacon for abolitionists and an Underground Railroad destination for Missouri freedom seekers. The nearby New Bethel AME Church was a hub for abolitionist activity, and figures such as teen Caroline Quarlls and John and Mary Jones.

Freedom to Equality tours take shuttles to explore Underground Railroad sites and other places steeped in Black history around the area. The home of 13th Amendment author Sen. Lyman Trumbull and a monument for abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy at the Alton Cemetery are among the points on the two-hour tour.

There are stops along the way to get off the bus and explore some of the sites. Make sure to check out the sole Miles Davis statue in the nation (he was born in Alton) near the visitor center and the Mississippi River on the west side of the city.

Address: Tour starts at the Alton Visitor Center, 200 Piasa St., Alton

Hours: Tours run from 10 a.m. to noon or 1-3 p.m. on the third Saturday of the month from September through November.

What to know: The cost of the two-hour tour is $32.50, but the shuttle bus is not ADA accessible. The tour goes through hilly areas of Alton and some cobblestone streets, which could make for a bumpy ride.

Amenities: Restrooms in the visitor center; free parking down the street with a three-hour time limit. Additional parking available throughout downtown Alton. Shuttle is not ADA accessible.

Phone: 618-465-6676 or 800-258-6645, riversandroutes.com/events/freedom-to-equality-tours-2023

Camp Warren Levis

Now a Boy Scout campground, this area was one of the first where freedom seekers from Missouri crossed into Illinois. Part of Rocky Fork, it was a stop on the Underground Railroad as early as 1816 and for at least a half-century after.

Address: 5500 Boy Scout Lane, Godfrey

Hours: Call for an appointment.

More info: 618-567-4407

Hamilton Primary School

Built in 1835, Hamilton was the first free and integrated school in the nation and a stop on the Underground Railroad, according to local lore. The current building was erected in 1873 with stones from the original building used in the building’s base.

The school is near a monument to Dr. Silas Hamilton, who founded the school along with George Washington. The monument was built on behalf of the formerly enslaved Washington, whom Hamilton raised as his own. Hamilton had freed Washington, along with 28 other African Americans.

The school was operational until 1971, when the school board decided to close it. A farmer until his death, Washington left money in his will to set up a scholarship fund for the education of African Americans. He also willed $1,500 for a monument to be built as a tribute to Hamilton. The scholarship fund is still going strong, and Washington and Hamilton are buried side by side.

Address: 107 E. Main St., Otterville

Hours: Call ahead to schedule a tour.

What to know: Tours need to be scheduled in advance. The school is in a rural area about a 20-minute drive from Alton. If you go during warm weather, be forewarned there is no air conditioning. There is a festival scheduled Sept. 23-24, and according to Sonny Renken, president of the Otter Creek Historical Society, visitors often reserve the school for overnight supernatural experiences.

Amenities: Restrooms, parking, not ADA accessible

Phone: 618-971-8503, 618-535-0342; hamiltonprimaryschool.com

Quinn Chapel AME (Brooklyn)

Missionary William Paul Quinn helped found the church, which was built in 1825. It’s possible that “everywhere he went and every church he established became an Underground Railroad stop,” said Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, author of “Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance.” Illinois AME churches in Chicago, Brooklyn and Alton are among them. Brooklyn’s cemetery is said to be the first Black cemetery west of the Alleghenies. Freedom seeker Priscilla Baltimore built her home in Brooklyn in 1851. This year, Landmarks Illinois listed Brooklyn as an endangered site, and efforts are underway from a local historical society and outside agencies to make sure the town remains on the map.

Address: 108 N. Fifth St., Brooklyn

Hours: Call ahead for information on visiting.

What to know: Parking is available on the street and in nearby lots. The church is in a rural residential neighborhood, about a seven-minute drive to East St. Louis, Illinois, and a 15-minute drive to St. Louis. Brooklyn is approximately a four-hour drive from Chicago.

Amenities: Partially ADA accessible; restrooms

More info: 618-271-6917, blogs.illinois.edu/view/7923/1436671013

Additional southern Illinois sites with no existing physical structure or closed to public: Kimzey Crossing/Locust Hill, Old Slave House (Crenshaw House),

Rocky Fork Area

For a half-century or more, this part of southern Illinois near Alton and just across the Mississippi River was a major gateway for formerly enslaved people into a free state. Many of the freedom seekers got established in the community as well.

Address: 2400 Rocky Fork Road, Godfrey

Hours: 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 1-3 p.m., third Saturdays of each month September through November.

What to know: Freedom to Equality shuttle tours through the Great Rivers and Routes tourism bureau will include a visit to the Rocky Fork Church, one of the verified Underground Railroad sites near Alton. Note that the shuttle is not ADA accessible. Tickets are $32.50 and begin in Alton.

More info: 618-465-6676, riversandroutes.com/directory/rocky-fork-area; riversandroutes.com/events/freedom-to-equality-tours-2023