For years, Rockford resident Atwood Forten Jacobs carried around his family Bible wrapped in wax paper and bubble wrap to make sure silverfish didn’t get to it. He said he knew its importance, and he didn’t want it to get damaged.

But it wasn’t until his then-school-age daughter was on the hunt for a book report subject that Jacobs suggested writing about their ancestor James Forten, a free man in Philadelphia who was a business owner, a philanthropist and an abolitionist.

At the library, he and his daughter stumbled across Julie Winch’s book, “A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten.” His daughter got an A on the book report, and Jacobs got an in-depth look at his great-great-great-great-grandfather’s significance in American history.

Jacobs reached out to Winch to tell her about his Bible, which lists the births, deaths and marriages of family members, some of whom eventually migrated west. Jacobs landed in Illinois. In sharing that material, his family tree become more real.

“I think the earliest entry is 1812,” Jacobs said. “It was given to James Forten’s daughter-in-law in 1839, Jane Vogelsang Forten, the day of her wedding.”

Jacobs donated the Bible to the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, where it’s on display as part of the “Black Founders of America” exhibit through Nov. 26.

“James Forten was an amazing man, very focused,” Jacobs said. Forten ran a sailmaking company and was one of the few Black business owners in Philadelphia. Funds from his company went toward abolitionist endeavors, such as running publications and advancing Philadelphia’s free Black community.

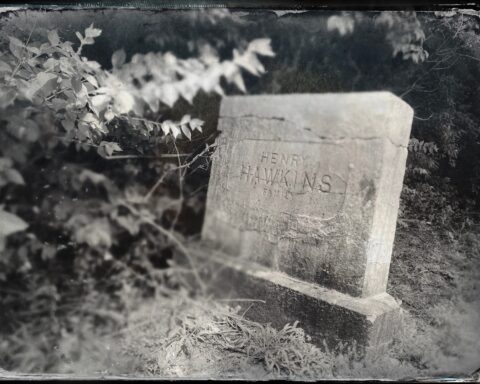

Jacobs donated the Bible for its continued preservation, so others can see the history — like the story of Ben Brown, a freedom seeker from Mississippi who spent months in the Wood River Valley of Illinois and found a life in Brighton, Illinois.

It’s that kind of history that folks like former teachers Glennette Tilley Turner, Charlotte E. Johnson and Larry McClellan, and Springfield resident James Ransom have dedicated thousands of hours to researching and promoting.

Lifelong history holders

Turner, 90, has written a dozen children’s books about history and the Underground Railroad. The Wheaton resident’s work as a historian, teacher, lecturer, consultant and community activist was recognized this year by the Illinois State Historical Society.

Turner’s book “The Underground Railroad in Illinois” is considered a primer on the area’s history, and she has a book about Harriet Tubman coming out in 2025 that includes an interview with Tubman’s great-niece. Turner is always on the lookout for a connection, a story on the Underground Railroad. Digging for details on the Underground Railroad gives her a sense of place to know history happened all around.

“It’s the untold stories that I’m interested in,” she said. “To find that Illinois was involved and then to find locations … there are just so many that tell such incredible things.”

Turner wants to know more about those people who watched the streets at night to make sure freedom seekers stayed safe when the Fugitive Slave Act was law. How would they alert the freedom seekers if something seemed odd or slave catchers were in the area?

“I think of Chicago as being unique,” Turner said. “Boston and Philadelphia and Cincinnati boasted as being safe havens, but I found in Chicago that Black and white abolitionists and people of different denominations and lines of work worked together in a harmony that I didn’t see in other cities.”

Johnson, a researcher, genealogist, teacher and historian, said she came to the field of research naturally. As the youngest of her cousins, she said listening to her grandparents’ stories and her father’s memories was inevitable, but her inquisitive nature about the events that “shaped lives” solidified her passion for the work. The Illinois State Historical Society honored her with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2021 for her decades of work.

Johnson, 90, married into a family whose farmland had been owned since the mid-1800s. Raised in Springfield, a former Chicago teacher and current Alton resident, Johnson shares what she learns, including the details of the history surrounding Rocky Fork, abolitionists and freedom seekers.

When the mantle of preserving her family’s history was passed to her by her late aunt Rose Marie Schultz Ashford, Johnson ran with it. Her research turned up a family publication that ran from 1820 to 1995. The photo on the cover of 1993’s publication “Illinois Generations: A Traveler’s Guide to African-American Heritage” showcases Johnson’s father-in-law at the 50th wedding anniversary celebration of James and Matilda Ballinger in 1810.

Johnson’s daughter Reneé helps with her history work these days. Sitting at a table with the pair, one learns so much, including more about the only ordained Black Baptist minister in Illinois at the time, John Livingston, who would organize several Black Baptist churches throughout Illinois, including in Chicago, under the teachings of Friends to Humanity, that would help with Underground Railroad activities.

“The Underground Railroad couldn’t happen without white folks who believed,” said Reneé Johnson. “In this part of the world, they didn’t get a lot of notoriety. Everybody probably knew, but they didn’t seek notoriety either, and neither have their descendants. But you have a man like James Lemen who, so much hinged on his being here. … Elijah P. Lovejoy wrote a newspaper and got his press thrown in the river.”

Lemen established anti-slavery churches in the area and trained Livingston.

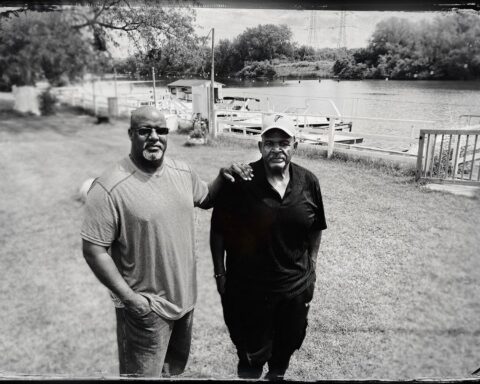

For Crete resident McClellan, the history of the Underground Railroad has been a research mainstay for over 20 years. Involved in civil rights activities in 1960s Southern California, he would go on to attend the University of Ghana in West Africa. He said both inspired him to dig deeper into issues of racial justice. His connections with Governors State University led him to working with the Black community south of Chicago, which subsequently led him to references to the Underground Railroad.

McClellan, 78, has written three books on the Underground Railroad, including the new release “Onward to Chicago: Freedom Seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois.”

McClellan and the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project helped get the Jan and Aagje Ton Farm designated as a site on the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom in 2022. He was the principal researcher for two other Network to Freedom sites in Crete and Lockport. His efforts were recognized in 2022 by the Illinois State Historical Society.

McClellan hopes his new book reframes the narrative of the Underground Railroad from one that centers on white Americans’ efforts to one that centers on the Black lens.

“The power in the Underground Railroad stories is the power of the freedom seekers,” McClellan said. “Our history is right here. It’s present and for all of us, that is a racially diverse history.”

When discussing the Illinois Underground Railroad, the name James “Terrry” Ransom is mentioned more than once. Johnson remembers him as her Girl Scouts leader’s son, but he too got the research bug when it came to Underground Railroad history. He chalks up his interest to his father, who taught him about civil and human rights, and his grandmother, who taught him about Abraham Lincoln.

Ransom used to traverse the state as an Illinois Department of Transportation employee, and he and friends would take pictures of places that were connected to the history. Ransom would then spend his evenings in libraries, gleaning details on the area. He spent over 25 years doing so. Ransom’s maps of Illinois Underground Railroad sites are still found in piles of documentation that Turner and Johnson have.

“A lot of times librarians knew other people that were knowledgeable in the history and they’d make phone calls and go by and talk to them — that worked out pretty well,” Ransom said.

Ransom remembers giving many talks and presentations through the years on the Underground Railroad and he said some people would get up and leave after hearing Illinois was a “free state” only in name, not in practice. With the Black laws, freed Black folks were very restricted to prevent them from moving to the state.

Ransom said some audience members don’t like to hear or accept anything bad about Abraham Lincoln.

“Illinois is still one of the most prejudiced states you will find,” Ransom said. “You go to Mississippi and you can find just as many towns in Illinois that are just as Black-hating. Have you ever read some of the comments that (Lincoln) made when he was down in Charleston at the Lincoln-Douglas debate? They fit right today. ‘I’m not going to make jurors, voters or anything else out of Black people. And if we have to live together, there must be a superior and inferior, and I approve whites to be the superior,’ something to that effect.”

Underground Railroad task force

To connect the dots around Illinois pertaining to the Underground Railroad, legislators recently passed a bill that will create a temporary task force Jan. 1. The group will develop a statewide plan to connect existing local projects and new projects to create a cohesive statewide history of the Underground Railroad in Illinois, and create new educational and tourism opportunities. The task force will review research, existing infrastructure and projects, and best practices to present recommendations to the General Assembly and Gov. J.B. Pritzker by July 1.

Turner, Johnson and McClellan all want to be involved with the task force, which was the brainchild of Tazewell County Clerk John Ackerman. The Washington, Illinois, resident said the task force will be an umbrella of sorts to show the full breadth of the Underground Railroad in the state and make that information more accessible.

“We do a good job of telling the story of the Underground Railroad through Illinois in little regional pockets — Alton, Jacksonville, Knox College. That does a disservice to the memory of the Underground Railroad,” Ackerman said. “The idea is not just regional projects that we know about, but finding undiscovered stories. This project is to drive local individuals, so that local history groups can start to add their story and context to the larger picture so that we can finally see the full breadth of what took place, the full length of that journey that they (freedom seekers) were on. They’ll be able to see where the pathways were, where these homes were located, and be able to take that journey themselves. And that’s the aspect where we promote education, but also historic tourism.”

Ackerman said he believes over 800 freedom seekers traversed Tazewell County. He said until two years ago, he was ignorant of Illinois’ connections to the Underground Railroad. Then he learned one of his ancestors had stayed with conductor Uriah Crosby. That ancestor bought property near participants in the Underground Railroad.

State Sen. Mike Simmons, a North Side Democrat, said that having recognition of the Underground Railroad, specifically Illinois’ prominence in the Underground Railroad is long overdue. As someone who has branches of his family tree in Michigan as early as 1846, Simmons said his ancestors probably used the Underground Railroad network.

“It’s a fascinating point of reflection that Black Americans found a way out of slavery before emancipation through the backcountry and waterways and swamps and thick forests and hostile terrains of several American states largely of their own agency,” Simmons said.

State Sen. David Koehler sponsored the bill after Ackerman brought the idea to him in 2022. He said that although it is a simple idea, he’s never had a piece of legislation take off as quickly as this one. He said everyone wants to be a part of it. “This is an issue that really brings us together as a state,” he said.

State Rep. La Shawn Ford, 8th, said this endeavor is a reminder that we as a state and society have to go further. “Every time we see these museums, these sites remind us of how the Black race was broken,” Ford said. “Is it enough to just be reminded that we were broken, or do we repair it? The way they’re doing the asylum-seekers, that’s what we were doing. And that’s why these asylum-seekers are being taken care of.”

State Sen. Mattie Hunter introduced a bill in 2005 to create a commission to study the trans-Atlantic slave trade and its effects on African Americans. The study’s data has been used to update materials outside of Illinois, she said.

“Everybody’s learning from this, so let’s teach them,” Hunter said. “I hope and pray to God that it will lead to reparations. Black people all over the world are talking about reparations.”

From stories to movement

If more in-depth awareness and knowledge are presented to all going forward, how does that translate to specific Underground Railroad sites? A number of ideas are in the works.

McClellan is doing what he can to gather local and state organization partners to create a Chicago Detroit Freedom Heritage Trail, which will commemorate freedom seekers’ journeys from one city to the other. Travelers will make their way through Bronzeville, stopping at Quinn Chapel AME in Chicago and then start on the Sauk Trail, sharing stories at the sites along the way. His goal is to then connect Illinois’ historic Underground Railroad sites and stories to those in northwest Indiana and Michigan.

As an author of historic site designations in Milwaukee and Michigan, Kimberly Simmons, a descendant of St. Louis freedom seeker Caroline Quarlls, is working on making the Detroit River a UNESCO World Heritage Site. She wants to get the river on the 2027 designation list because thousands of freedom seekers used it on their journeys.

Gerald McWorter is a great-great-grandson of “Free” Frank McWorter, the first African American to establish a planned community in the U.S. with New Philadelphia, Illinois. McWorter said there’s talk about developing a Corridor of Freedom along Illinois Highway 72 by February. Kate Williams, McWorter’s wife, said the corridor’s purpose is to help people further understand why this region was called a “honeycomb with abolitionism.” She said the corridor will highlight the diversity of historically rural America and the role Black people played.

“It’s a moment to take charge of what is the Black abolitionists’ history in Illinois, and how it can be presented to people, because I don’t think anyone has really asked that question,” Williams said. “And with the corridor, we’re beginning to ask it.”

McWorter said his great-grandfather Solomon married a woman from Springfield, and the correspondence that highlights those types of connections is the focus of this emergent corridor.

“All of these towns are connected; that’s why we’re developing this Corridor of Freedom,” he said. “Between Abraham Lincoln in Springfield and Mark Twain in Hannibal, Missouri, is Jacksonville, Pittsfield, Barry, Quincy. Looking at the six cities, there is a set of museums, all of which have exhibits on New Philadelphia. The corridor will link together Underground Railroad sites, the historical development of Black communities in all of those places, as well as in each case, their connection to New Philadelphia.”

Brooklyn, Illinois, has an ongoing campaign to preserve its existence. Declining population, a limited economy and tax base, and loss of land due to railroads, have placed Brooklyn on Landmarks Illinois’ endangered list this year. Regional advocacy manager Quinn Adamowski said his organization is working closely with the town’s historical society to make sure the area remains on the map.

“What we’d like to do here in the very near term is put together a task force of people … that can help bring together a plan of action for Brooklyn,” Adamowski said. “The more this story gets out there, the more likelihood there is for resources to come, whether they be financial, human capital.”

With the Underground Railroad task force on the horizon in Illinois, Adamowski said it’s important to have regional representation. “The task force presents a huge opportunity for communities across the state,” he said.

Former historical society president Roberta Rogers has passed the baton to Robert White III. Former Attempts by Brooklynites to leave their mark on the area with marked pavers have been thwarted in the past, but plans continue. Quinn Chapel AME pastor Aurelia Jackson said she dreams of opening a small Freedom Village in the lot next to the sanctuary for kids to learn the Underground Railroad history at their level.

National Park Service Network to Freedom

This year marks some notable occasions for the Underground Railroad: the 100th birthday celebration of Mary Ann Camberton Shadd Cary, an anti-slavery activist, the first Black woman publisher in North America, the first female publisher in Canada, and the second Black woman to attend law school in the U.S.; the 100th North Buxton Homecoming, a celebration over Labor Day weekend that brings freedom seekers’ descendants to the area; and the 25th anniversary of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, which has hundreds of significant locations, programs and monuments.

The landmark designations all started with Vincent deForest, his brother Robert deForrest and their creation of the Afro-American Bicentennial Corp. When the brothers, who spell their last names differently, found that only three sites related to Black folks existed on the register for landmarks of over 1,500 nationwide, they did something about it. By bringing notable athletes into the Civil Rights Movement, the Ohio siblings forged a corporation that would nominate Black history sites as landmarks to the Department of the Interior National Park Service.

At 87, deForest, recalls the work as one of inclusivity. “I find it very difficult to stand still when things are happening around me, particularly when I think that I know better,” deForest said. “Freedom is not something that has meaning in just this country; it has meaning all over the world, in one form or another. All of this plays into that.”

To ensure that historical preservation continues, deForest said we must ensure that youths have an appreciation for the value of the work that was done before them.

“Getting that work into the classrooms, that’s all of our responsibility. It’s more than just Ron DeSantis,” deForest said. “I think that there is a movement of forces that don’t want to see this happening; it is our new Civil Rights Movement right in front of us now. But the government can’t do it. We are the government.”

Barry Jurgensen, Midwest regional manager of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, works with local communities and a 13-state region to promote the preservation of Underground Railroad sites. Jurgensen walked from Nebraska to Chicago to raise money to fight modern-day slavery in 2016. Since started his current job in November, he has seen his first nomination, the Israel and Avis Blodgett House in Downers Grove, make the list.

“We invite communities to help us grow what we collectively know about the Underground Railroad by going back into their local histories, identifying people of African descent who lived in their communities in the 19th century to the early 1900s, and researching those individuals’ stories,” he said.

According to Jurgensen, the biggest issues facing the Underground Railroad sites are finding the resources to restore and maintain historic buildings and creating the next generation of stewards.

He hopes the Illinois task force will bring more attention to the stories of free Black communities and freedom seekers, as they were the nucleus of the Underground Railroad. He also hopes that more research on the role of women is brought to the fore.

“These are the stories that are the most elusive to discover. The documentation is there; it always has been, we just have to find it,” Jurgensen said. “Communities, their youth and local area experts are critical to unlocking this history and are always an important element in many initiatives to preserve and promote the Underground Railroad.”