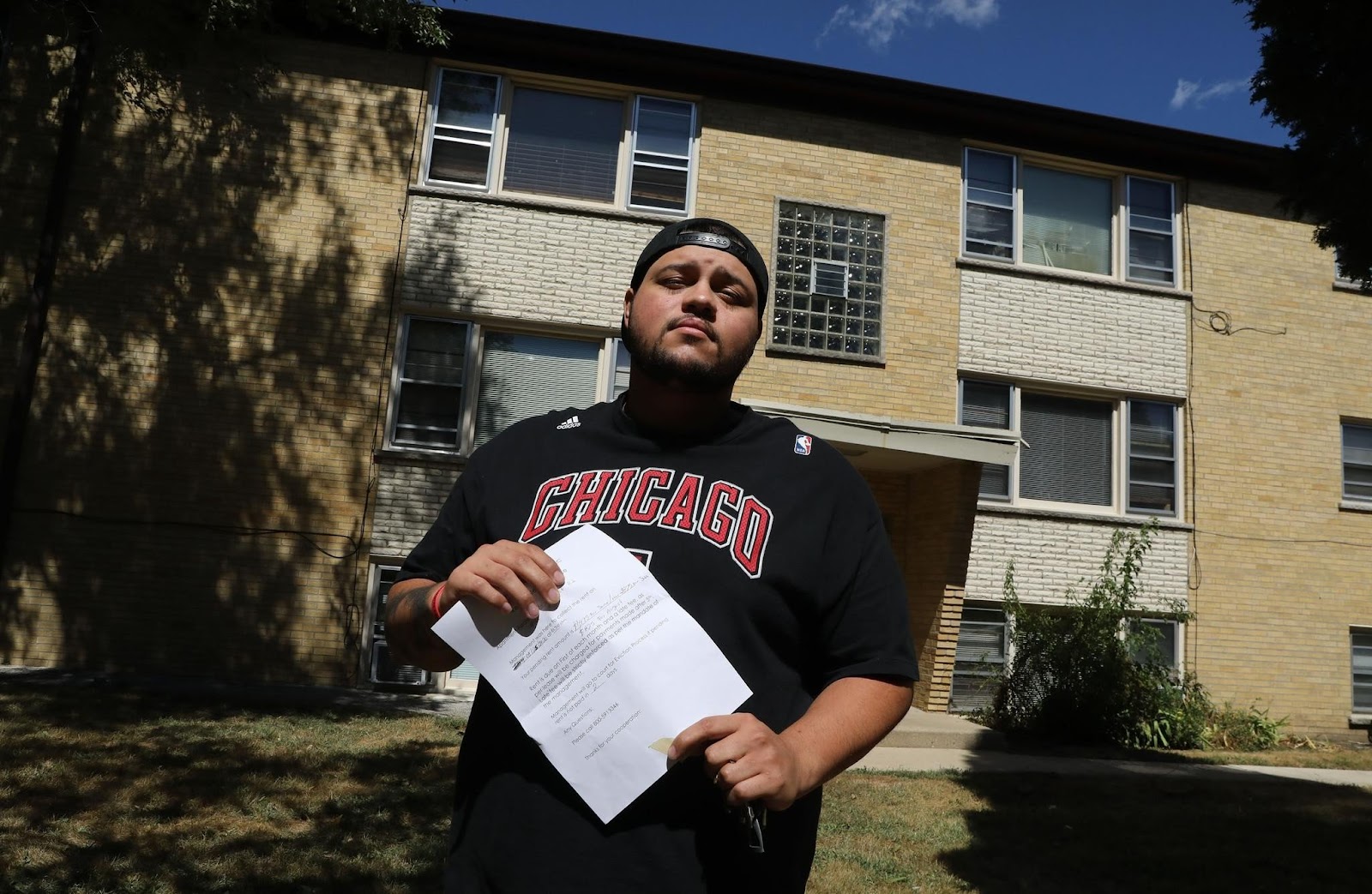

Before the pandemic, Jaime Espinoza, 28, was making ends meet with DJ and security jobs. Working under the moniker DJ WrcksIt for eight years, the Hillside resident went from clearing almost $50,000 in 2019 to, this year, hosting $5 open mic showcases in Melrose Park to cover his $850 monthly rent, car payment and groceries.

After informing his landlord that he would have trouble paying rent in April, Espinoza started receiving notices on his door saying he had days to come current. When the landlord told him they would change the locks, he asked his family for money to keep him afloat. But he still owes thousands of dollars in back rent.

“I tried to come up with a payment plan to pay down what I owe, but work’s still been slow,” he said. “It seems every week, (building management is) knocking on my door and giving me notices that I have five days left to pay what I owe. I’ll make a $300 payment, and then they’ll leave me alone for a couple days, then knock on my door again.”

Changing the locks would be an illegal lockout, and the state’s moratorium on evictions means Espinoza can’t be forced from his home until the crisis spurred by the coronavirus has passed.

But his experience is all too familiar for some Illinois renters, who find themselves in housing limbo as they struggle to pay rent due to the financial constraints brought on by COVID-19. And despite Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s latest extension on the statewide eviction moratorium (currently set to expire Sept. 19) and a federal halt on some evictions through 2020, some people continue to receive warnings of evictions that can seem like the real thing.

“I’ve kind of just been avoiding them at this point, because there’s not much I can really offer,” Espinoza continued. “I guess I’m just kind of waiting for the point where they get fed up and send a county sheriff to my door and tell me I have to go.”

And, despite it all, evictions are still happening.

In Cook County, there were 3,339 eviction cases filed between March and August, according to county officials. Although the cases cannot proceed through the courts and be carried out by a county sheriff until the moratorium is lifted, landlords have filed the paperwork necessary to start the process as soon as they can.

The number of cases is in line with records independently kept by tenant advocates like Conor Malloy, who oversees the Rentervention project with the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing. He’s been keeping a record of eviction filings from Legal Aid Chicago, and although the moratorium has led to far fewer eviction cases compared to 2019, his count is in the thousands, as well.

“Even in a ‘good’ economy with single-digit unemployment, we had about 14,000 evictions filed by this time last year (in Chicago),” Malloy said.

His tally of Cook County eviction filings for March through August stands at 2,704 cases, with 73% filed in Chicago. His numbers could differ from the official count because he’s using public-facing data, which might not include things like sealed cases related to foreclosure, Malloy said.

And those are just cases that have been officially filed — the tip of the eviction iceberg, advocates said. There could be more than a half million renter households in Illinois at risk of eviction because of the economic impact of COVID-19, said Bob Palmer, policy director of the nonprofit Housing Action Illinois.

Nationally, one in three renters owed back rent at the start of September, with Black and Latinx renters more likely to have rent debt, according to a new report from apartment listing platform ApartmentList.com.

Nearly half of Latinx renters surveyed and 41% of Black renters surveyed still owe rent from spring and summer. Among those in arrears, many said they are making tough decisions to stay afloat, with 30% running up credit card debt, 31% selling off assets to make ends meet, and 16% dipping into their retirement savings.

Even when formal evictions are off the table, landlords still have options in their toolboxes for wayward tenants, Malloy said. Illinois requires landlords to give tenants five days’ notice that they intend to pursue eviction for nonpayment of rent, allowing renters those five days to catch up before their landlord can file for eviction in court.

The legality of serving those notices when evictions currently aren’t allowed is unclear, he said. To some, an eviction proceeding begins when the court case is filed, while some advocates say the eviction notice should count as commencing an eviction proceeding and be similarly prohibited.

In other eviction cases, landlords must provide 10 days’ notice for issues such as violating the lease agreement or causing damage. If a lease is month-to-month or bound only by a verbal agreement, tenants are to receive 30 days of notice.

In Albany Park, Ferrus Najemba, 34, is facing her third eviction in a decade. After moving into her two-bedroom apartment with her teenage daughter in January, she and the other tenants of the seven-unit apartment building at 3746 W. Leland Ave. were told in May that the building had been sold, and they would need to leave by the end of June.

The building’s new owner, Brian McFadden, told tenants the building was closing for repair work. Although his company initially said it would be “unable to renew” the leases, it issued a statement saying it had not filed for any evictions, given anyone an eviction notice, or taken other actions to remove residents.

“On the contrary, the (company) has offered support for the tenants’ relocation by bringing in a bilingual relocation professional with experience in helping low-income families find new housing,” according to the statement issued by BRM1, McFadden’s limited liability company.

Originally from Uganda, Najemba has lived in Albany Park for 10 years. While she doesn’t want to leave the neighborhood, she said she’s going to look somewhere else for her next apartment, because she feels like even if she gets a new apartment nearby, she’ll “probably go through the same thing.”

“I can’t be on the street right now,” she said. “This is a bad time. People have taken down all their (for rent) signs, because they don’t trust who is coming in. Why are you leaving? Probably you have COVID. Maybe you lost a job, you don’t have money — that’s why they kicked you out.”

Since June, all the tenants have stopped paying rent, said Victor Muñoz. Muñoz lives in the building with his wife and two children; the younger one, who is 9, has asthma, he said.

“It’s a business. I get it,” he said. “But, the uncertainly of knowing if I’m going to have a roof over my kids — I need to provide for that.”

In hopes of delaying their exit from the Leland Avenue building, Muñoz and his neighbors worked with the Autonomous Tenants Union, a Chicago-based housing justice collective, to form a tenants union and request one-year leases for current residents.

On Sept. 4, the group was out in front of their building calling on McFadden to come to the table and find a solution that would work for everyone.

“When we got the eviction notices, it was heartbreaking (and) scary. I was angry,” Muñoz said after the protest. “We are willing to negotiate with him. We’re willing to get him rent — as long as he negotiates with us and meets with us, face to face.”

In addition to offering relocation help, BRM1 initially offered to return tenants’ security deposits and their June rent payments if they were out of the building by the end of June. BRM1 suspended that decision around the same time it started receiving threatening calls and tenants stopped paying rent, said BRM1 spokesman Clint Sabin.

One week after the demonstration, Sabin said Thursday that the company would offer the Leland Avenue tenants the one-year leases they asked for — but not until they pay their back rent, which now totals four months’ worth.

But that’s unfair, said Jake Marshall, an organizer with the Autonomous Tenants Union who has helped the Leland Avenue tenants.

“You can’t have it both ways; they actually have no legal obligation to be paying rent until BRM1 rescinds this 30-day notice,” Marshall said. “Either collect rent from your tenants and let them live there, or tell them they have to move and accept (that) once your notice expires, they don’t have to pay rent until they’ve vacated. They have no legal obligation to pay rent if they don’t have any active tenancy.”

When tenants receive 30-day notices, most leave out of fear, said Philip DeVon, an eviction prevention specialist with the Metropolitan Tenants Organization (MTO) who attended the Sept. 4 event.

Such notices are not included in the state’s eviction moratorium. DeVon calls them “invisible evictions.”

“We know from experience that the majority of evictions, which is just someone being dispossessed, a lot of those happen outside of the court,” he said. “And so there are untold numbers of people who are being displaced by 30-day notices today.”

MTO has seen twice as many calls about eviction since March compared to the same time period last year, even though Pritzker’s eviction moratorium went into effect at the start of the state lockdown, DeVon said.

The eviction moratorium “just means that they can’t be kicked out in the traditional sense, with a court order and the sheriff coming to enforce that order,” he continued. “I think a lot of people are just intimidated into silence, because it’s something where you’re vulnerable.”

Landlords are often at an advantage when it comes to understanding housing laws in Illinois, DeVon said. Most can afford to hire a lawyer and are well-versed in tenant law. They can also make it very uncomfortable for a renter to stay, he added.

“The landlord has power over your place of safety, your home. And when you know someone could just show up and pound on your door for you to leave? The landlords have power beyond that,” he said. “It’s just a huge power imbalance.”

But tenants and advocates are finding ways to fight back.

After much debate over who had the power to assist ailing renters, the Chicago City Council enacted the COVID-19 Eviction Protection ordinance in June. After receiving a five-day notice, a tenant can submit a notice that their missed payments are due to a coronavirus-related loss of income and enter into a seven-day negotiation period with the landlord. Before the landlord can continue with terminating the lease and evicting the tenant, they must participate in the negotiations in good faith.

One month later, the City Council passed the Fair Notice ordinance, giving some tenants more time to vacate if a landlord increases rent, doesn’t renew a lease or terminates a multiyear or month-to-month lease. Tenants who have lived in an apartment for six months to three years are allotted 60 days of notice, while those living in a home for more than three years are to receive 120 days’ notice.

But those laws don’t prevent tenants from being evicted without cause, advocates said.

In response, some are calling for a Just Cause bill, which would eliminate no-cause evictions, give more time to tenants, and also put restrictions on reasons a landlord can evict a tenant. If a landlord wants to move into the space themselves, they would be entitled to do so. But evicting a tenant in order to remodel the home and again lease it at a much higher price would be banned or restricted, DeVon said.

With such a bill, tenants like Muñoz and Najemba would be protected, Marshall said.

“People try to pretend this is not an eviction, because it’s just terminating a tenancy,” he said of the Leland Avenue situation. “They don’t actually have to provide a basis for why they’re (removing tenants) from the building, because they are month-to-month tenants. That’s what the Just Cause ordinance is saying: You do have to have a basis in order to do this.”

And renters who aren’t evicted will still owe back rent when the moratorium is lifted, DeVon noted.

“It doesn’t solve the problem of debt,” DeVon said of the eviction moratorium. “When the state moratorium or the national order by the CDC expires, we’ll be right back in the same place, with a bunch of renters who can’t pay rent — and potentially a lot of landlords who can’t pay their mortgage.”

At the same time, landlords, particularly those who own multiple properties, have been feeling the pain since March along with their tenants.

Manjunath Ramanna owns 36 residential properties in the western suburbs under the name R&R Luxury Realty. He said tenants have defaulted on $150,000 in rent from April to August.

His firm will be in court, seeking to evict at least 100 tenants who are behind on rent, as soon as the moratorium is lifted, Ramanna said. Many of his 386 tenants have applied for Illinois Housing Development Authority grants, but are still waiting while applications are processed.

“As a whole, we are not out there looking to evict tenants,” said Michael Glasser, a landlord and president of Neighborhood Building Owners Alliance, an organization that represents small and midsize property owners in Cook County. “We want to be responsive to those people, especially those who … have been impacted by COVID-19 to no fault of their own. We want to be as gracious as we can in trying to accommodate their needs, and that’s been the case since the get-go. (But) in order to do that, we need revenue.”

Glasser said the pandemic has hit neighborhood property owners, who own a small number of buildings, the hardest. Their profit margins tend to be smaller, which means they must figure out what sacrifices to make when money stops coming in, he said.

“The first step might be that they simply cannot afford to do pest control, or can’t afford to get their dumpsters emptied twice a week, or can’t afford to bring a roofer out,” Glasser said. “So, one of my concerns is a decline in the quality of the maintenance and cleanliness of buildings.”

And, once lenders come calling, landlords risk falling into foreclosure, he said.

“When the foreclosures start happening, my concern isn’t just for the owner, but for the tenants in that building that need affordable housing,” he said.

Such concerns are also on the mind of Derrick Rowe, a landlord on the South Side and a member of NBOA. After selling two single-family homes to financially maintain his remaining portfolio, Rowe now owns five properties he rents, along with his own home. His properties are part of his retirement plan, which he said is at risk due to the pandemic.

“In the beginning (of the pandemic), I didn’t think it was going to get this bad,” he said. “I’ve had to sell two of my homes … just to have funds to pay my bills and taxes on my other properties. So, it’s gotten really bad for me.”

Rowe said he’s had to put off maintenance requests because he simply can’t pay for the repairs.

“I used my credit card and half of my personal savings to stay afloat,” he said.

Despite the home sales, Rowe is still $12,000 behind on his mortgage payments, and he said it’s very difficult to get loans for some financial relief. Through all of it, Rowe said he is still trying to provide for his tenants, but it’s challenging. He wishes there was more help for landlords.

Glasser said mortgage relief doesn’t even begin to solve the problem. While the cost of owning and operating a residential property might eat up as much as 90% of a landlord’s rental income, the mortgage only represents about 20% of those expenses.

“In the end, the banks are only going to go so far,” he said.

Rowe said it’s hard for him to help people when he can’t get help himself to maintain his properties.

“I understand if you’re not working, you can’t pay your bills, but I don’t think I should lose my property either,” he said. “Why is it OK (for) this person not pay rent, but I have to pay my mortgage?

“This is another question I love to ask my tenants and other tenants out there,” Rowe said. “If I lose my properties to the bank, and the bank eventually does an eviction, now we’re all out on the street. So, is it really helping that I lose my property?”